FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. — Arkansas’ tree growth is outpacing removals, but the abundance doesn’t just signal a rich timber supply. It also increases the risks for disease, pests and wildfires. A trio of researchers took a deeper look at the gap and the factors behind it.

By Maddie Johnson

University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture

Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station

Striking a balance between forest growth and removals is key to keeping forests sustainable, according to Sagar Godar Chhetri, assistant professor of forest economics with the College of Forestry, Agriculture and Natural Resources at the University of Arkansas at Monticello.

Chhetri and his fellow forestry researchers found that Arkansas’ forest growth-to-drain ratio averaged 1.63 over the last decade, meaning forest volume is increasing. The ratio is calculated by dividing net timber growth by timber removal, which includes harvests.

A ratio of 1.0 would indicate a balance between forest growth and the removal of forest products.

“It also serves as one of the determinants of sustainability,” said Matthew Pelkki, a professor and economist with the Arkansas Forest Resources Center and co-author of the study. “As long as the growth-to-drain ratio does not consistently stay below 1.0, there will be a continued long-term supply of timber resources in the region.”

As a partnership between the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture and UAM, the Arkansas Forest Resources Center conducts research and extension activities through the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station and the Cooperative Extension Service, the Division of Agriculture’s research and outreach arms.

Pelkki is also director of the Arkansas Center for Forest Business, a part of UAM’s College of Forestry, Agriculture and Natural Resources.

Over the last four decades, the ratio has ranged from 0.66 to more than 2.5 in the southern United States. However, the study noted that the underlying factors affecting this ratio were poorly understood.

The Journal of Forestry published their findings in a study titled “Factors Affecting Forest Growth-to-Drain Ratio at Sub-regional Scale in Arkansas, USA.”

Sustainability and economic opportunity

The ratio is a gauge of forest sustainability, Chhetri noted, which, by its simplest definition, means not removing more trees than are growing. Tree removals can be caused by humans — from timber harvests to building and road development — or by natural causes like hurricanes, drought, insects, diseases and wildfires.

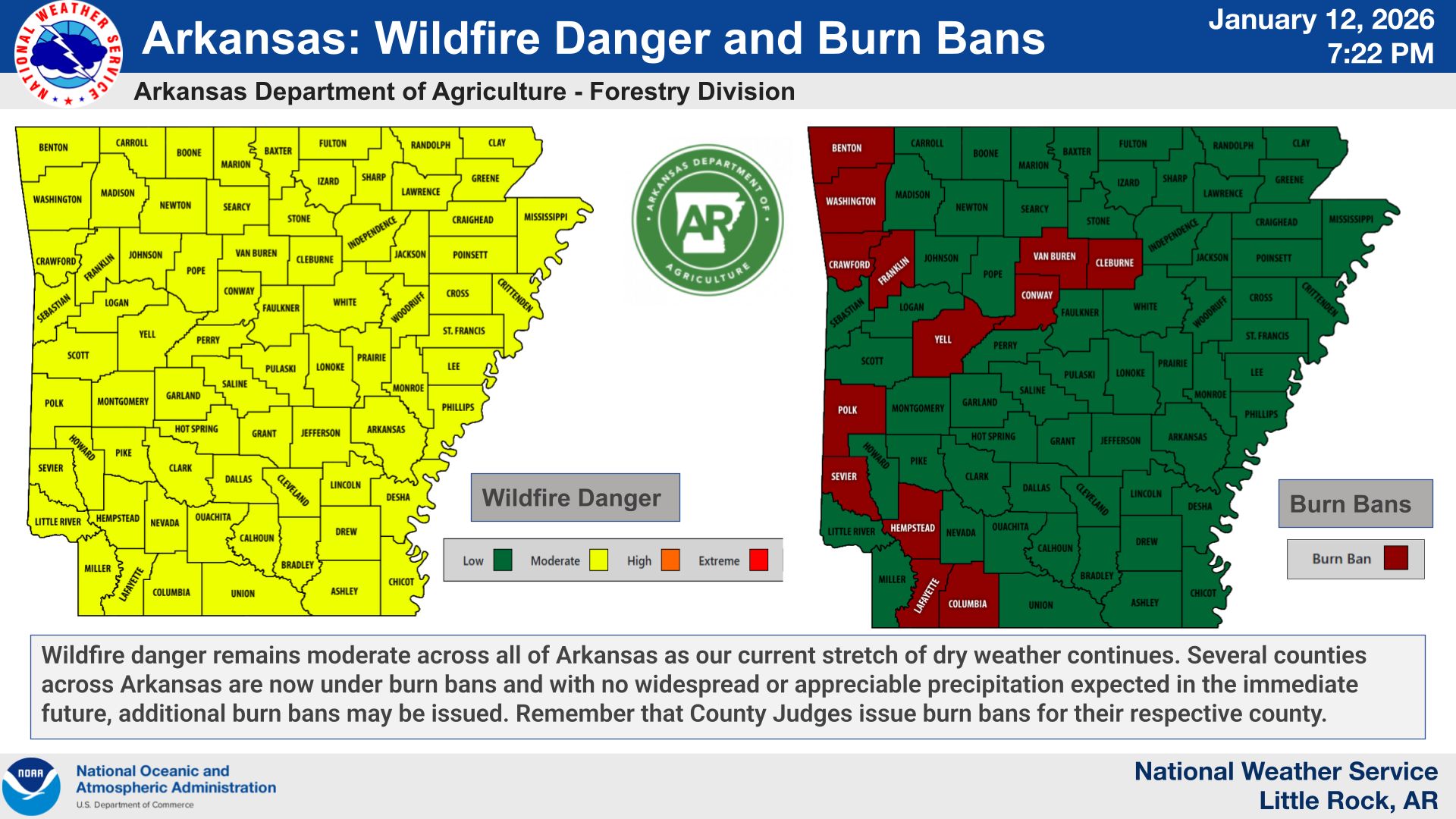

If too many trees are removed, forest sustainability becomes imbalanced. Forests can’t provide enough timber for building materials and pulp for paper products or offer environmental benefits like improving water quality, increasing carbon storage and providing wildlife habitat. On the other hand, Chhetri said dense forests are more prone to wildfire devastation from the accumulation of dead, flammable woody fuels.

The Arkansas forestry sector contributed an estimated $4 billion to the state’s gross domestic product and supported more than 26,000 jobs in 2023, according to the Arkansas Center for Forest Business’ latest fact sheet on the state forestry industry’s economic contributions.

“The data on growth-to-drain can help determine locations for economic development efforts by identifying regions where the supply of timber is more than adequate for additional timber harvesting and manufacturing of wood products,” said Pelkki.

Investigating the ‘why?’

Researchers examined how the growth-to-drain ratio compared among Arkansas’ four ecoregions, finding the Mississippi Alluvial Plain has the highest ratio while the South Central Plains has the lowest. So, the quantity of trees is lower in the Mississippi Alluvial Plain than in the South Central Plains because agricultural lands mostly dominate the Mississippi Alluvial Plain while most of the fast-growing pine and wood processing mills are in the South Central Plains, Chhetri explained.

“With these findings, forest managers can identify areas where increased harvesting is ecologically beneficial,” Chhetri said.

When it comes to conservation efforts and forest management, Chhetri pointed out that the two aren’t mutually exclusive.

“They must be done simultaneously,” he said.

A targeted approach

The researchers call for outreach programs to help promote landowners’ active management of forestland.

“Passive conservation alone can lead to overstocked forests, which are more vulnerable to wildfires, insects, diseases, and prone to ecological imbalance and missed opportunities for economic development,” Chhetri said.

Pradip Saud, an assistant professor of natural resource biometrics with the Division of Agriculture’s experiment station and UAM’s College of Forestry, Agriculture and Natural Resources, was also a co-author of the study.

To learn more about the Division of Agriculture research, visit the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station website. Follow us on X at @ArkAgResearch, subscribe to the Food, Farms and Forests podcast and sign up for our monthly newsletter, the Arkansas Agricultural Research Report. To learn more about the Division of Agriculture, visit uada.edu. Follow us on X at @AgInArk. To learn about extension programs in Arkansas, contact your local Cooperative Extension Service agent or visit uaex.uada.edu.